Design Sprint in Gubbi

My journey as an AIF Clinton Fellow placed with a start-up social enterprise in rural Uttarakhand began in September. Here’s a day in the life.

|

|---|

| A coconut farm in a village near Gubbi. |

The alarm rang at 5:30 AM. It was Thursday, Oct 3rd. My project supervisor Sheeba and I were headed to a village near Gubbi in Karnataka, a regional business hub for surrounding small villages. We had planned to take the train, however, delays up to two hours were expected. We took the bus instead, arriving in just under three hours. Harshita, our translator and local guide, met us at the Gubbi bus station. Sheeba and I were just as foreign in this part of India, none of us knowing how to speak Kannada.

Today was a field day to interview farmers. For the past month, Sheeba and I have spent everyday at Third Wave Coffee Roasters, a coffee shop with a friendly co-working environment. We were preparing a deck to pitch to investors by mid-November. I had been researching about the carbon credit market, completing market sizing and competitor analysis, and preparing documents on regulatory frameworks. For context, the carbon market is split into two segments: voluntary ($191 million USD) and compliance ($70 billion USD) [1, 2]. In an effort to reduce carbon emissions, select countries implement carbon emission mandates on companies and industries. A prime example is the emission trading scheme set up by the European Union [3]. Still, many companies such as Lyft or Etsy seek to reduce their unavoidable emissions voluntarily through the purchase of carbon credits [4]. Sheeba was interested in leveraging the cash available in these schemes to fund massive afforestation – pursuing the mission of the social enterprise she co-founded.

|

|---|

| Typical desk setup at Third Wave Coffee Roasters. |

We were in Gubbi that day because we wanted to determine the needs of farmers. To enable massive afforestation, there needs to be the labor or forest stewards to plant and maintain forest ecosystems. Sheeba has been working in Uttarakhand for the past seven years, with the most recent two years heading Alaap, one of the American India Foundation’s partners that I am now supporting as an AIF Clinton Fellow. Her organization has been exploring afforestation as a means to improve livelihood and climate resiliency for mountain farmers. However, with project based funding, she was never going to scale afforestation to the level needed to address climate change nor reach to the farmers in need of greater livelihood. She moved to Bangalore, the tech and investment city of India, with the hopes of creating a business model to enable massive scale afforestation; in other words, to scale up Alaap. In developing a business model, we wanted to know whether or not farmers would even use the product we would create.

To answer whether or not farmers would use the product we were planning to create, the most important aspect is that we solve real and actual needs. Although Sheeba worked extensively with farmers, we needed to check whether or not her field experience and familiarity with mountainous communities translated to farmers in other regions such as Karnataka. I suggested using a design thinking framework to Sheeba; the same framework used by the Stanford d. School and Frog Design. I had taken classes on design thinking, completed workshops, and led design thinking for groups. I went to the local store, purchased some permanent markers and packs of post-its. I brought it back to Sheeba’s house, set up a small design space on the second floor of her apartment, and we delved into a mini design sprint. The power of design thinking to elucidate assumptions and as a means to dig deeper into product development became immediate.

We took our design thinking mindset to Gubbi that day to understand the daily lives of three farmers stratified according to wealth: rich, middle, and poor. I conducted two of the three interviews. The goal was to generate stories to see what tensions, contradictions, or surprises exist in their stories. We had them walk us through their lives starting in the morning to the moment they sleep. One farmer had a deep moral dilemma. He knew that using chemical fertilizers on his land was damaging the fertility of his soil, however, he was not willing to give up the lifestyle afford to him from using chemicals. With chemicals, he could harvest 240 coconuts from one tree versus 80 coconuts without the use of chemicals. To contrast, another farmer only did natural farming. What was interesting was that he was using Fukuoka style of farming which means no till and no fertilizer. I had read the One-Straw Revolution by Masanobu Fukuoka years ago and had never thought I would come across a Fukuoka style farmer [5]. He was also experimenting with a Miyawaki style forest, the same type of methodology that Alaap uses in Uttarakhand. At the last end of the spectrum, we interviewed a landless farmer. The two farmers we had previously interviewed had about ten acres of land each. A landless farmer would fall under the category of an extreme user. We listened to him talk about the difficulty of finding work, being shouted at by his employers, and his dreams of one day earning more money. By interviewing the extremes of wealth, we can then choose one user to design for. Often times, by addressing the needs of an extreme user, the design can translate to solving the needs of the mass.

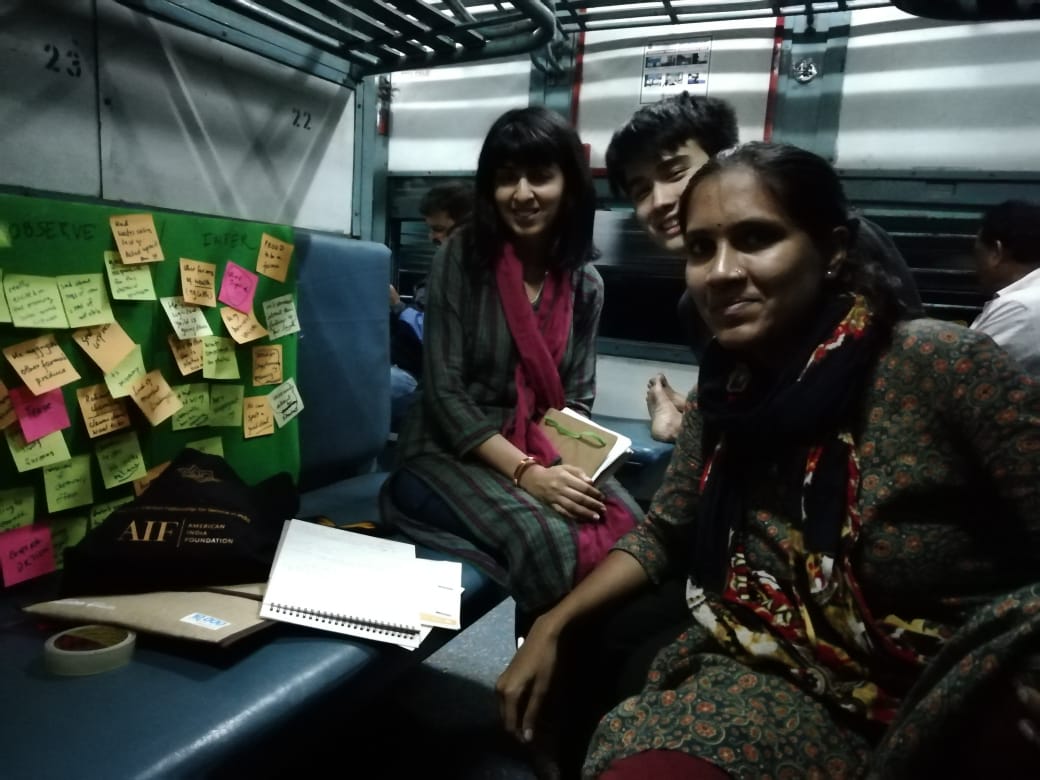

After nearly five hours of interviews, we boarded the train back to Bangalore and debriefed each farmer by listing out our observations and then making inferences from those observations. We kept particular attention to surprises, contradictions, and tensions that came from our dialogues. Our colleague Harshita was able to detail the nuances from the interviews and played a large role in the design process.

|

|---|

| Debriefing an interview with a farmer on the train ride back to Bangalore. Pictured from left to right: Sheeba, me, Harshita. |

When we finished our debriefs, Sheeba felt that we could use more interviews with farmers in a different region to gain a more thorough understanding of Karnataka. This week, we are headed to Belgaum, a 13-hour train ride away, to undergo a design sprint with the farmers that live there. We plan to undergo one iteration of prototyping while we are there. We will be joined by Harshita again and a designer named Sapta.

At the same time of interviewing farmers, we have just completed our interviews with CEOs and heads of multi-billion dollar international industries to small business owners in Bangalore. A large source of funding comes from businesses. An interesting trend we are noticing is that sustainability is no longer just a corporate social responsibility branch of a company; sustainability is moving into the space of becoming a large part of the company brand. We have also noticed a repulsion of the word offset, in relation to the purchase of carbon credits. For many companies, offset is the last resort and connotes the imagery of pay to pollute. We will use data such as this when we begin to approach the challenge of scale. First we solve the needs of the farmer and what we create, will need to be scalable.

This month of work has exceeded my expectations. Sheeba has been a very encouraging colleague, mentor, and advisor. In the upcoming months, I am excited to build the beginnings of a social enterprise with her.

References:

- Hamrick, K., & Gallant, M. (2018). “Unlocking Potential: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2017.” Forest Trends.

- The World Bank. (2019, August 1). “Carbon Pricing Dashboard.” Retrieved from https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/map_data.

- Convery, F. J. (2009). “Origins and Development of the EU ETS.” Environmental and Resource Economics, 43(3), 391-412.

- Greene, S., & Façanha, C. (2019). “Carbon Offsets for Freight Transport Decarbonization.” Nature Sustainability, 1-3.

- Fukuoka, M. (2010). The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming. New York Review of Books.