Design and Systems Thinking for the Climate Crisis

| Social Enterprise Building @ Clinton Fellowship in India | 2019 |

Part of my work as a Clinton Fellow at a nonprofit called Alaap has focused on providing frameworks for key stakeholders that can help solve the climate crisis to engage with systems and design thinking. In order for these frameworks to create lasting and meaningful impact, they need to be able to bring common understanding and reveal compelling system level interventions. Our guiding principle is: wisdom is in the room.

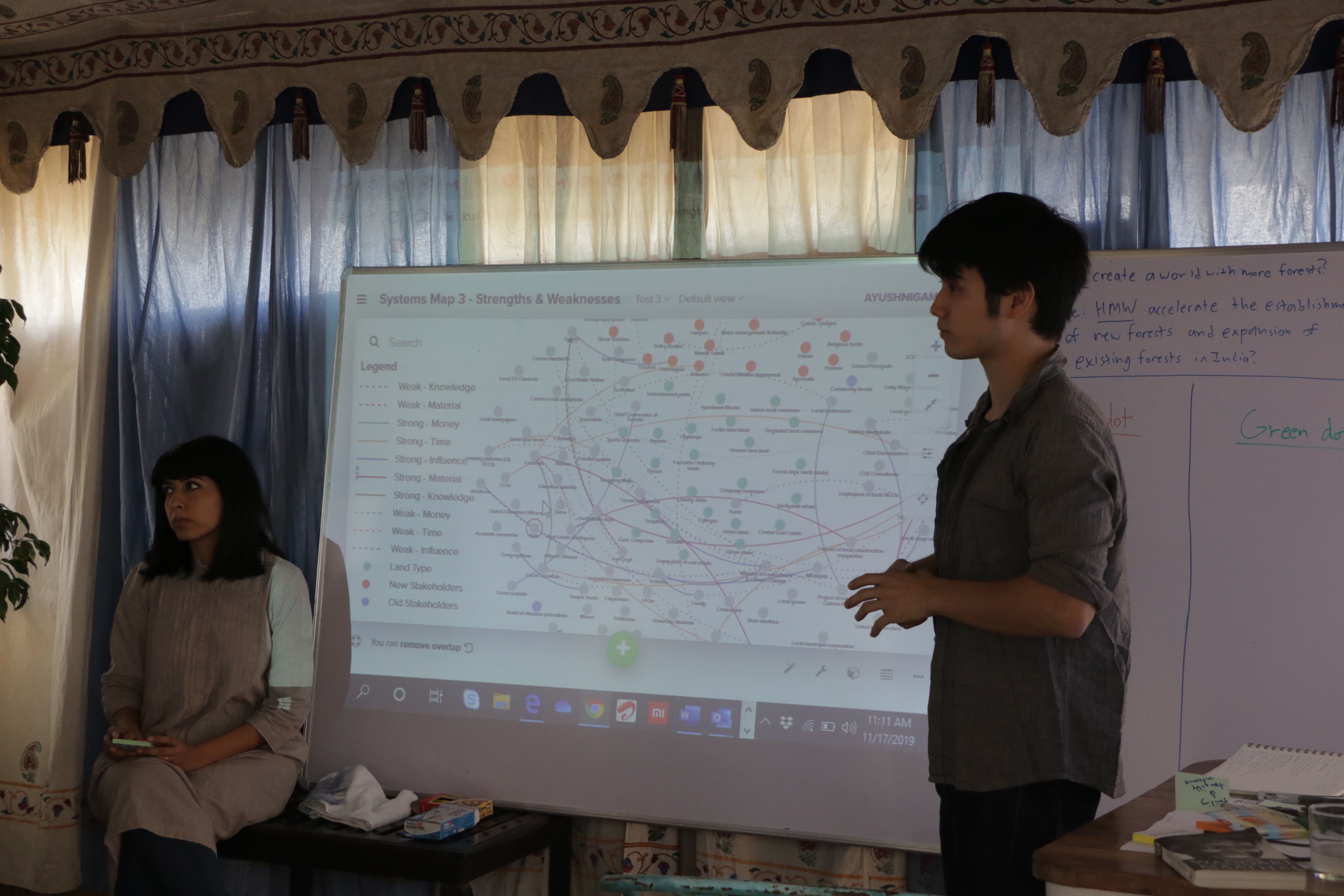

One adaptation of a World Cafe I led brought together five stakeholders representing government officials, corporations, urban architects, education directors, and farmers to help answer the question of how might we create a world with more native forests, restricted geographically to India. With the help of Peter Coughlan and Ariel Raz, I created a framework that guided stakeholders through creating a series of three system maps and identifying the leverage and opportunities in the system. The highest level of intent was to build trust by listening to all stakeholders.

We started by providing the frame:

“407.4 ppm is the amount of CO2 in our atmosphere. Our actions are leading to rising sea levels, suffocating cities, and plummeting biodiversity. Our rural populations are hit especially hard with unseasonal rains, extreme weather, and desertifying lands. Forests is one technology to sequester our carbon dioxide, to reduce global surface temperatures, and restore urban & rural livelihood. The IPCC states one billion hectares of forest is needed to help us stay under 1.5 C of warming. How might we create a world with more native forests?””

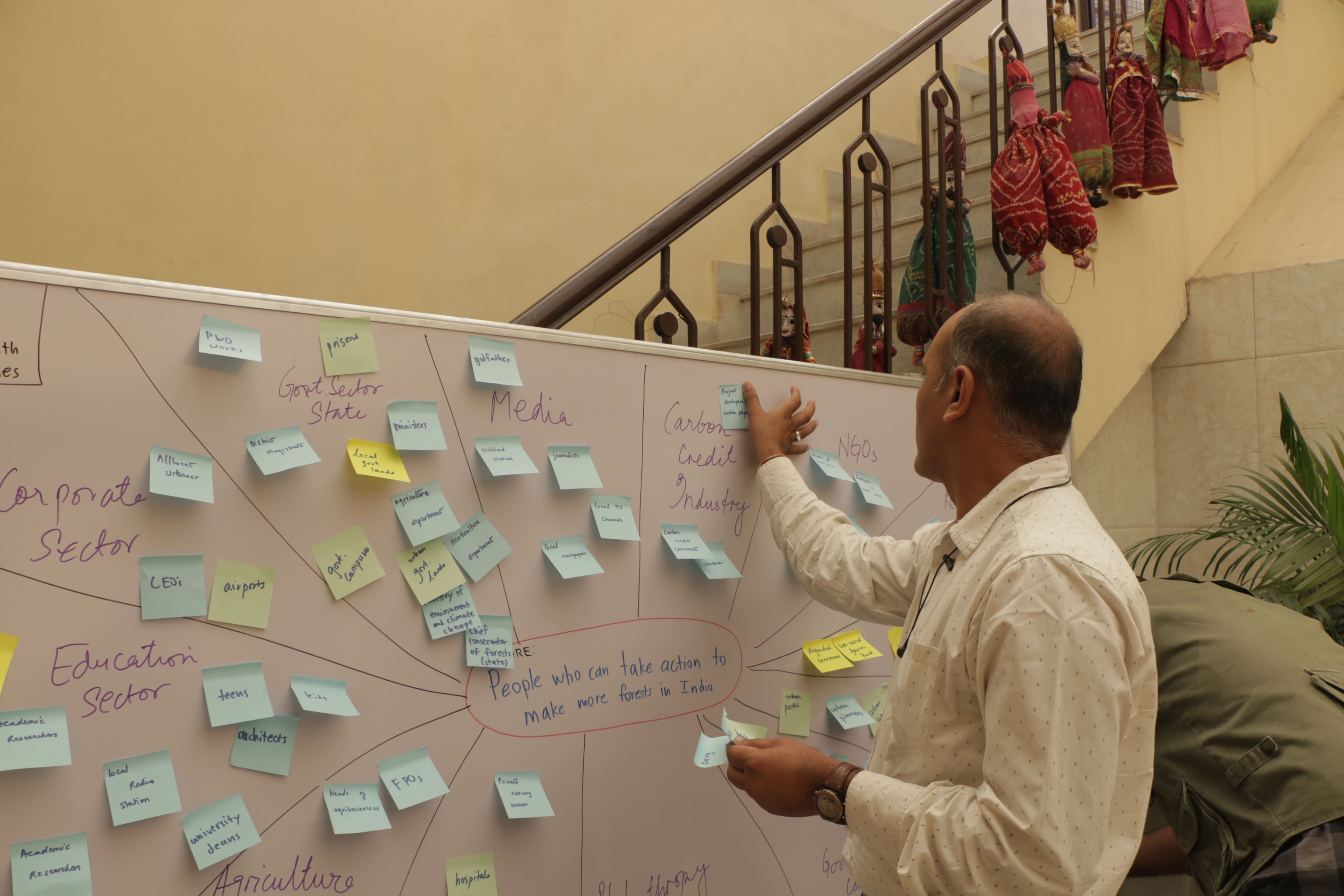

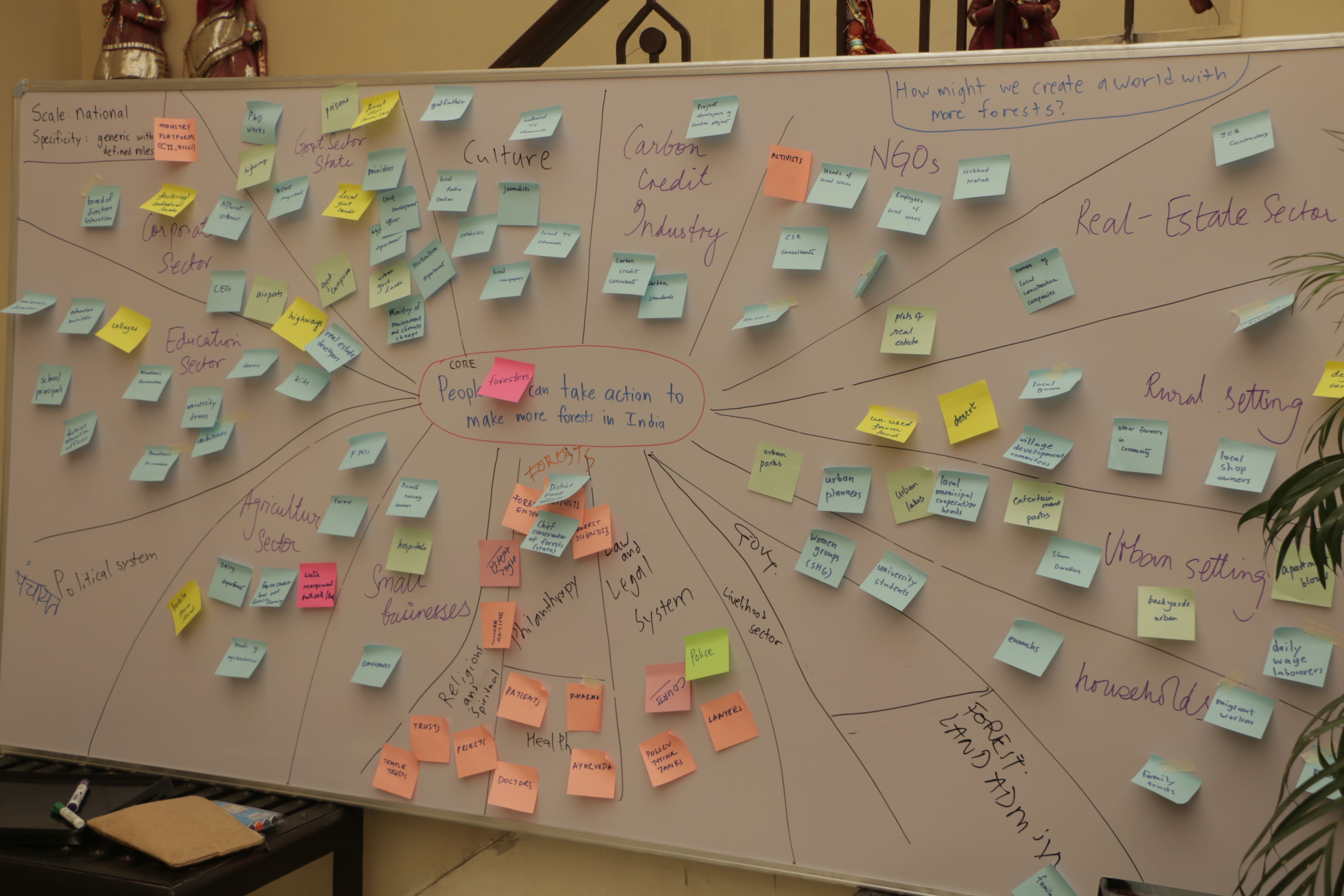

For the first systems map, we asked participants to place the post-its of the relevant stakeholders and physical settings that can support a forest onto the subsystem on the board.

We then asked stakeholders to refine the map; adding, subtracting, or creating new subsystems. A total of 98 stakeholders were generated and categorized into 19 subsystems.

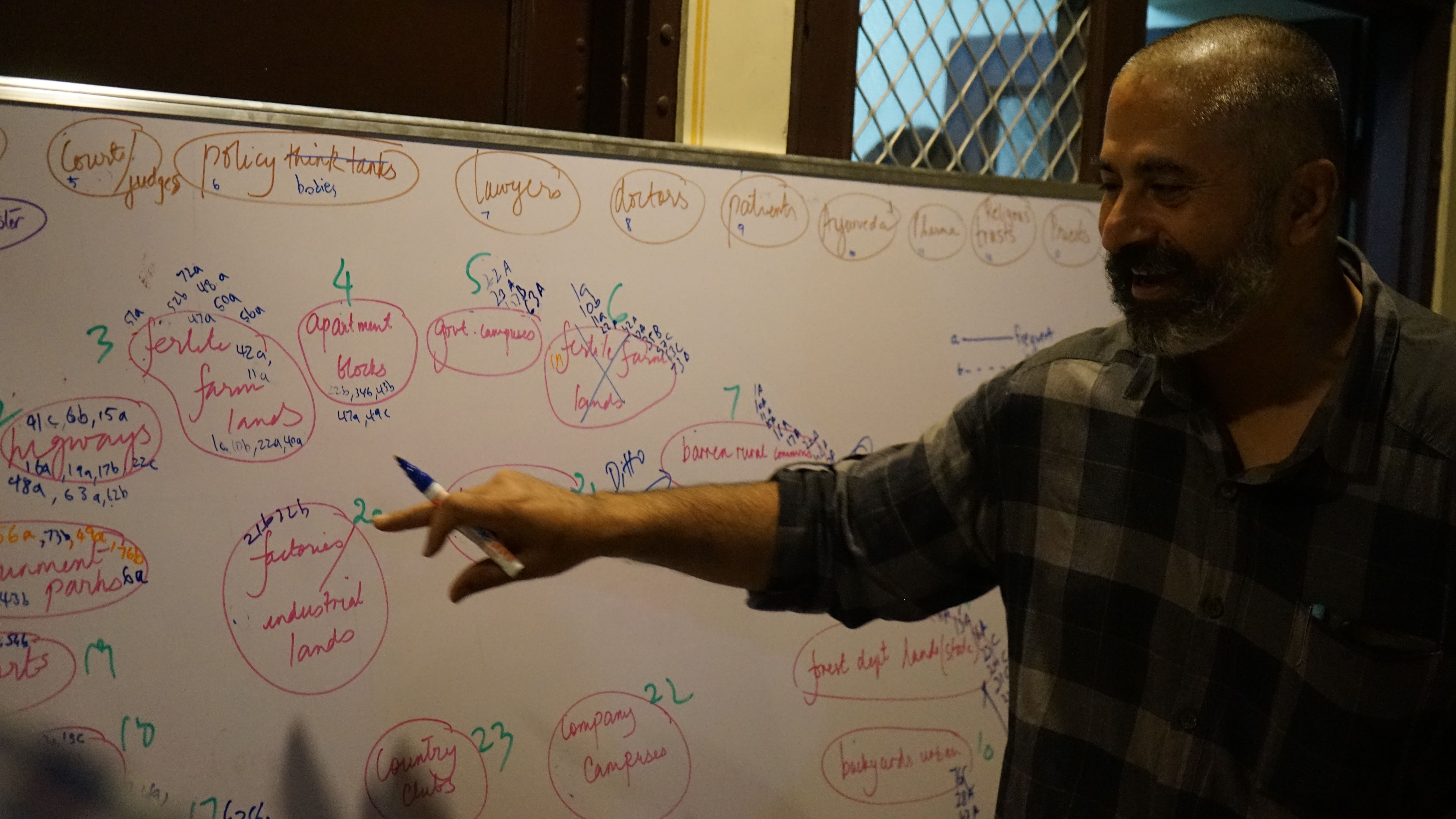

For the second map, we split the group into two and asked each group to connect each of the 23 land parcels with stakeholders that occasionally or frequently interact with the land and also to identify the decision makers on these lands.

We then had participants combine their maps onto one board using a coding system since every line drawn created inertia.

For our last map, participants were asked to identify the five strongest or established and five weakest or emerging relationships in the system. In each relationship, participants were asked to note the exchange of one of the following values: knowledge, influence, material, money, or time.

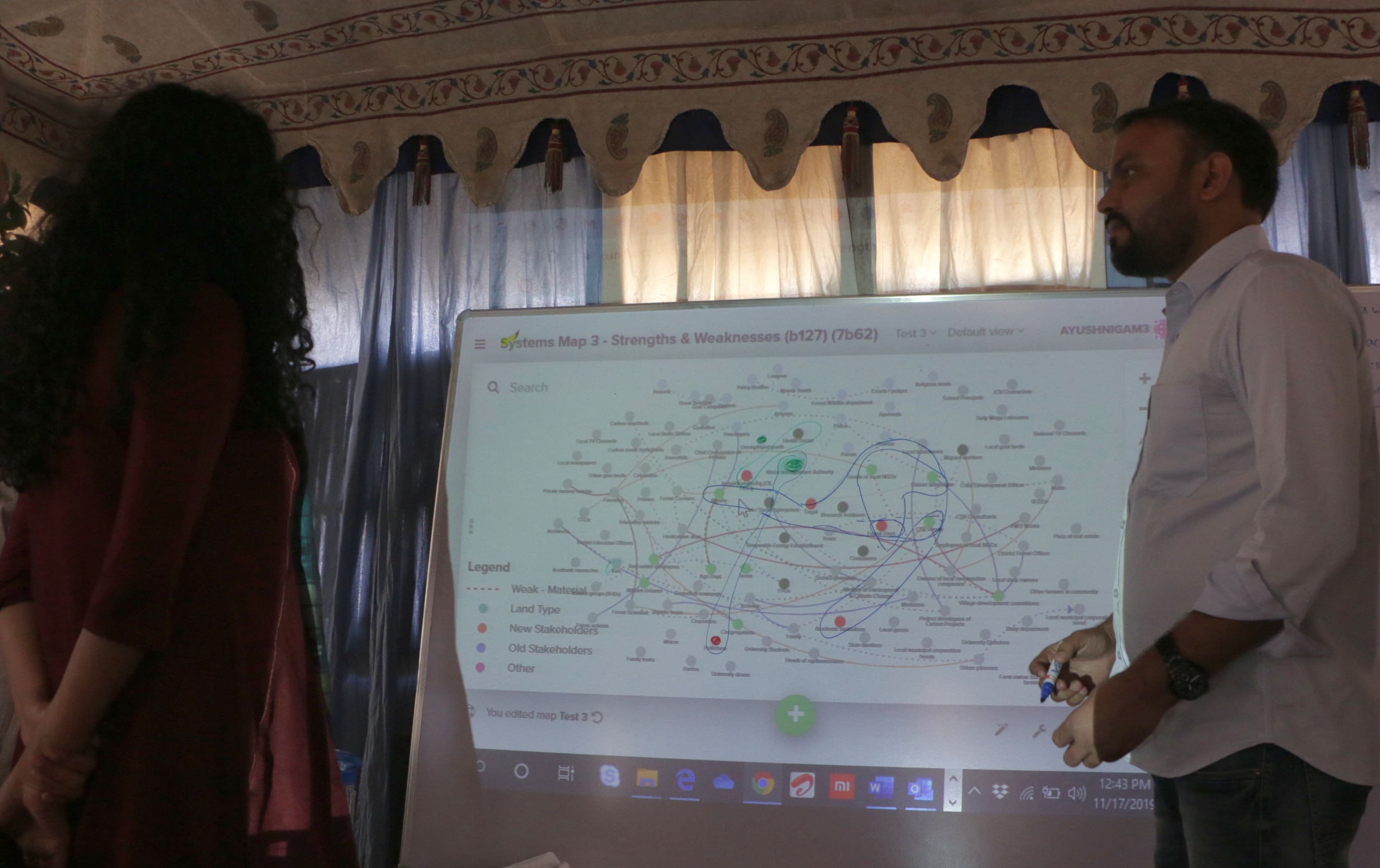

The next day, we began the debrief of our maps and moved into a discussion of leverage. Where is there positive energy in the system? Where are the barriers? What areas are frozen? What are emerging trends? Each participant was asked to identify three green and three red dots. Green dots represent positive energy or momentum in the system while red dots represent blockages, challenges, barriers, or gaps in the system.

Amoebas were drawn around the green and red dots, denoting potential leverage opportunities or opportunity areas for action.

Interact with our complete systems map here or on Kumu.

For our progress report click here.

Design Sprint in Belawadi, Karnataka

At Alaap, I also facilitate design thinking sprints to help us uncover the needs of the stakeholders within the system map.

To understand the needs of farmers, I facilitated a design sprint for our team at Alaap. Our group was inspired by Basavaraj, a 1.5 acre smallholder farmer who practices rain fed agriculture and is currently working as a daily wage labourer to supplement his income.

When we first met Basavaraj, we were surprised to notice that he became a daily wage laborer six years ago when a drought hit his farm. We wonder if this meant that he felt that he had no choice other than daily wage labor. We thought it would be gamechanging to give him more options to fulfill his financial needs that gave return in the short term, is easy to understand and to execute.

In 30 minutes, we created a contract that details a business scheme that pays farmers to lease 20% of their land for a 10-yr period in which a forest would grow in that space, guaranteeing consistent monthly income.

Basavaraj rejected our prototype, saying,

“My land is fertile. Why would I plant trees?”

Despite the assurance of a monthly income, our solution didn’t address his deeper need. Perhaps on a deeper level, it was really about food. Future iterations to come.

Design Sprint in Juliasar, Rajasthan

To understand how needs differ in different contexts, we traveled to the most desertified state in India, Rajasthan. There we met and were inspired by Laddu-singh, a 39 year old farmer and contractor/migrant worker with a 20 acre farm.

We were surprised that he said trees “are life”, are beautiful, inviting to guests and thinks if it can work on his friends farm, it could possibly work on his. When we asked him what kept him up at night, he said he doesn’t know how much longer his body can take the toil of being a migrant worker. We wonder if this meant that he needed a vision for himself back home. We thought it would be gamechanging if he could create beauty for a living on his land.

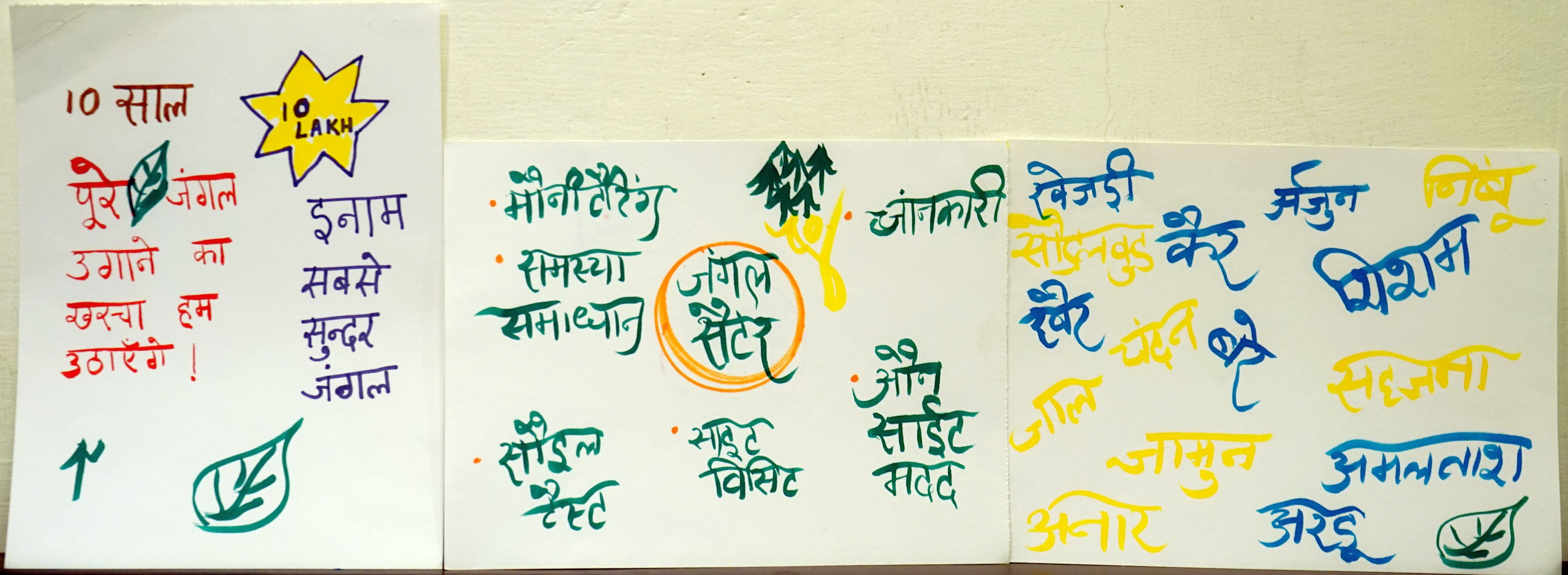

We created a pamphlet for a forest beauty contest, in which 80% of forest creation fees would be covered by a philanthropic company that wants to see more beautiful forests in the world. The other 20% would be an investment by farmers. At the end of ten years, the company would come to select a winner for the owner of the most beautiful forest, the grand prize being ten lakhs rupees ($14,000). For fairness sake, forests would be judged based on the climatic conditions of each region. We said there were 12 climatic conditions in India. Last, there would be a local knowledge center to facilitate information exchange, guide farmers on how to create forests, and where they could get reimbursed. Strict accounting rules would be set for reimbursement. The contest does not guide farmers how to make income out of forests, but the local knowledge centers could give suggestions.

Six out of the six farmers we tested our prototype on wanted to start. Laddu-singh himself loved the idea.

It is important to note that many of the men in the village have turned to being a migrant worker. Perhaps what migrant workers like Laddu-singh need is an economically viable reason to return home to and be reunited with their families; the latter being a particularly strong need. What Laddu-singh also showed us was that beauty was also an unarticulated need.

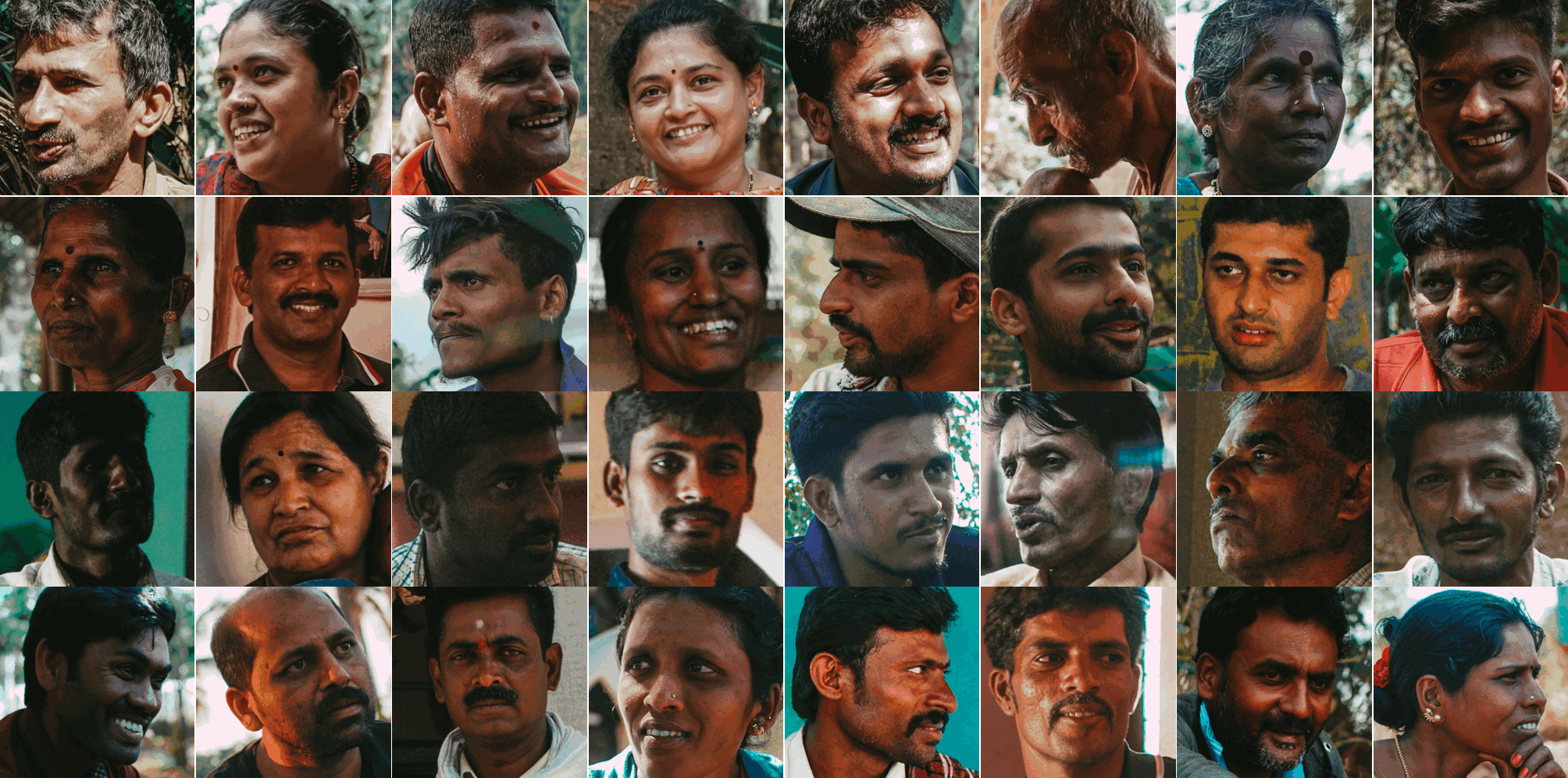

Ethnography Study in Karnataka

The last segment of my fellowship involved designing and leading an ethnographic study across two extreme regions (lush forests of the Western Ghats to dry regions of Bagepalli) of the Karnataka state of India. Over 70 farmers were interviewed. Please see part 1 and part 2.